SINGAPORE/BEIJING (Reuters) -China’s Communist Party meets this month to map a five-year vision that prioritises high-tech manufacturing in its quest to upgrade its sprawling industries and project global power as its rivalry with the U.S. intensifies, analysts say.

Known as a plenum, the meeting is also likely to pledge strong measures to lift household consumption and curb deep, historical supply-demand imbalances that threaten long-term growth in the world’s second-largest economy.

The two goals are decades old and pull in opposite directions, a policy challenge that has become acute now with U.S.-China tensions worsening, making it hard for Beijing to pivot to demand-side policies, analysts say.

Industrial prowess demands maintaining the status quo of channelling state resources to producers, while boosting consumption requires funds be redirected to households, leaving less for business and government investment.

FACTORIES VS CONSUMERS

China’s growth over the past decade was driven by the pursuit of the first goal at the expense of the second. But this action is now fanning deflationary pressures and creating unsustainable debts.

The intensifying rivalry between the U.S. and China, underlined by U.S. President Donald Trump’s renewed threats of triple-digit tariffs last week, has complicated matters for policymakers in Beijing, analysts say.

It’s a choice to prioritise great power competition over the compelling need to address domestic growth imbalances.

China’s next five-year plan, the closely watched policy document that the October 20-23 plenum will produce for parliamentary approval in March, will “definitely emphasise, and re-emphasise, support for high-tech research and industrial development,” said Chen Bo, senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s East Asian Institute.

“In terms of a country’s hard power, manufacturing is still a top priority,” Chen said. “When conflict arises, what ultimately matters is manufacturing, not services.”

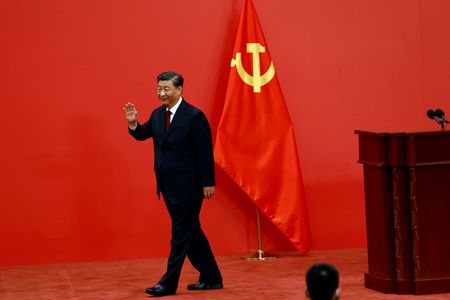

A speech by President Xi Jinping published by Communist Party magazine Qiushi in July said the world was going through changes not seen in a century, which made “technological revolution and major-country competition increasingly intertwined.”

Xi called on the nation to secure the “strategic high ground” in the global tech race.

China now leads in industries such as electric vehicles, solar or wind and is leveraging its dominance of rare earths production with export controls before potential trade talks between Trump and Xi later in October.

Apart from a few high-end sectors, such as aircraft or advanced semiconductors, its supply chains are largely domestic. With the West aiming to re-industrialise and re-arm after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and amid growing tensions over Taiwan and the South China Sea, the stakes are too high for Beijing to even contemplate slowing down on that front.

“If you do not develop high-end industries, you will be subject to others in the future,” said Guo Tianyong, professor at the Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing, warning, however, that China needed a better policy balance.

CRACKS ARE EMERGING

Morgan Stanley analysts said they expect post-plenum statements to deliver a “tech- and supply-driven framework, with incremental focus on social welfare.”

Consequently, “decisive reflation remains elusive in 2026,” they added.

Beneath the envy-worthy headline growth, the past five-year cycle has been anything but smooth sailing for the economy – factory gate deflation is becoming entrenched, adding to a property crisis, a municipal debt scare, endemic industrial overcapacity, and record youth unemployment.

A generation who studied for highly skilled and well-paid service sector jobs, which a consumption-driven growth model had better chances of creating, faces limited opportunities.”If you only rely on external demand and domestic demand is not working, then you will have unemployment problems and also deflation,” said Larry Hu, chief China economist at Macquarie.

“If it continues like this for one or two years, it’s still okay. But in the long run, it will definitely be a problem.”

Hu expects China to get serious about stimulating consumption if and when external demand shrinks enough to threaten growth targets.

EMPTY PROMISES ON CONSUMPTION?

The 2026-2030 blueprint will be China’s 15th five-year plan since it adopted Soviet-style quinquennial policy formulation cycles in the 1950s.

The 14th promised to “fully leverage the fundamental role of consumption in stimulating economic development.” The 13th pledged that “the contribution of consumption to economic growth will continue to grow.”

Yet Chinese households – their wealth eroded by the property crisis and confidence shattered by strict pandemic curbs – still prefer saving over spending, prompting calls to reform labour markets, taxes, state firms, land rights and welfare.

Analysts say China can muddle along with its contradictory goals by tilting industrial support toward tech research and away from capacity expansion, while gradually building on its incipient efforts to strengthen the welfare system.

Over the past year, Beijing has rolled out consumer goods subsidies, childcare benefits, and small pension increases. A recent top court ruling that makes social insurance contributions mandatory for both employers and workers lays the groundwork for stronger welfare over the longer term.

One policy adviser, asking for anonymity to discuss sensitive topics, said benefits will likely rise further in the next five years, with lower pensions increasing faster than higher ones.

But improvements “won’t be particularly substantial,” even though “everyone recognises the issue of insufficient demand,” the adviser said, adding that the small social security budget and tight local government finances limit policy options.

After the property sector’s downturn, the adviser added, “we are unable to find new demand drivers.”

Dan Wang, China director at Eurasia Group, expects the five-year plan to “focus more on people’s livelihood, including social security, healthcare systems, and possibly more support and protection for low-income groups.”

But, she says, such language should “absolutely not” be read as a paradigm shift.

“In a now very typical Marxist country,” Wang said, “it’s all about production.”

(Reporting by Claire Fu in Singapore; Ellen Zhang and Kevin Yao in Beijing; Writing by Marius ZahariaEditing by Shri Navaratnam)